In many programs we may wish to display graphics.

A typical notebook or monitor today has a graphical display with a resolution of 1920 x 1080 pixels. On almost every display each pixel's color is a combination of red, green, and blue components, each of which is an unsigned 8-bit value ranging from 0 to 255. For example, this blueish color has components red = 98, green = 160, blue = 234:

Sometimes we will represent a color using a string such as "#62a0ea", in which the red, green, and blue components are represented as 2-digit hex numbers. For example, 6216 = 9810, a016 = 16010 and ea16 = 23410, so this hex string represents the same blueish color we see above.

We can use a graphics library (also called a toolkit) to perform graphical output. Such libraries will allow us to draw low-level shapes such as lines, rectangles, and circles, and may also provide higher-level widgets such as menus, buttons, and toolbars that we can use to build more complex graphical interfaces. The term GUI (= graphical user interface) usually refers to a user interface of this sort.

Some popular cross-platform graphics toolkits include GTK and Qt. These are large and complex, and are accessible from many languages including Python. Most desktop applications that come with Ubuntu and other Linux distributions use either GTK or Qt.

Additionally,

there exist various Python-specific libraries including Tkinter

and Pygame. Tkinter is part of

the standard library in every Python installation, and includes many

widgets such as menus and buttons. Pygame is a popular cross-platform

library for creating real-time games in Python. Pygame doesn't come

with Python, but you can easily install it using pip.

If you're writing a desktop application such as a text editor or calendar program, Tkinter is probably a good choice because its widgets will be helpful for building your program's interface. On the other hand, if you want smooth real-time graphics, it may be better to write your program in Pygame. If you're implementing a turn-based board game and don't need widgets, either library could be OK.

This week we will discuss Tkinter. I've created a Tkinter Quick Reference page that describes the Tkinter classes and methods that we will use, as well as various widget classes that we won't have time to cover. For more information, the site TkDocs has a Tkinter tutorial and also points to the Tkinter reference pages. (The book Modern Tkinter is inexpensive and is also helpful, though it seems to contain just the same text as the Tkinter tutorial in PDF format.)

As a first example, let's write a Tkinter program that displays a window with a green circle:

We

will use a Canvas

widget,

which is

a rectangular area where you can draw any

graphics that you like. The

canvas widget is flexible and powerful. In fact, some Tkinter

programs might use only a single canvas widget inside a top-level

window.

A

canvas may contain various items

such

as lines, rectangles, polygons, ovals, text, or images. Each

canvas item represents

a shape or image, and has an

integer ID. Each canvas item has various options

which

you can set when you create an item, and which you can modify later

using the itemconfigure()

method

of the Canvas

class.

Here is the program:

import tkinter as tk

root = tk.Tk() # create a top-level window for the application

root.title('circle')

canvas = tk.Canvas(root, width = 400, height = 400)

canvas.grid()

canvas.create_oval(100, 100, 300, 300, fill = 'green', width = 3)

root.mainloop() # run the main loopLet's look at the program line by line. We first import the tkinter library using the convenient abbreviation "tk".

The Tk()

constructor creates a

top-level window

for your application.

Typically we store this window in a variable called "root".

You can call the .title()

method on the top-level

window to set its title.

We next

create a canvas

widget and specify values

for two options,

namely width and

height which

determine the canvas's size. To make the

canvas visible, we must

call canvas.grid() to

register it with the grid geometry

manager

(otherwise known as a layout

manager),

which determines the

positions and sizes of widgets in a window. We

will learn more about grid layout in a following section.

The call

create_oval()

creates an oval item, which

is an ellipse (of which a circle is a special case). This program

draws an oval whose bounding

box is the square

with (100, 100) at its upper-left corner, and (300, 300) at its

lower-right corner. We specify two canvas

item options,

namely fill,

the color with which to fill the oval, and width,

the width of the outline in pixels.

Finally,

we call the mainloop()

method which tells Tkinter

to run the main loop for our program. Typically any graphics library

has such a main loop, which waits for events

to occur and

dispatches them to handler functions. In this first program we don't

handle any events; we simply display graphics and wait for the user

to close the window. Nevertheless we must still call mainloop().

Let's modify our program so that it will create a new circle each time the user clicks the mouse. We'll give each new circle a random color. Here's the updated program:

from random import randrange

import tkinter as tk

root = tk.Tk() # create a top-level window for the application

root.title('circle')

canvas = tk.Canvas(root, width = 400, height = 400)

canvas.grid()

def on_click(event):

# choose a random color

red, green, blue = randrange(256), randrange(256), randrange(256)

color = f'#{red:02x}{green:02x}{blue:02x}'

canvas.create_oval(event.x - 50, event.y - 50, event.x + 50, event.y + 50,

fill = color, width = 3)

canvas.bind('<Button>', on_click)

root.mainloop() # run the main loop

In this program, on_click()

is an event

handler function

that we want to run whenever the user clicks the mouse. We call the

.bind() method

to register this

event handler to run in response to the <Button>

event. (You can read about

other event

types in our quick reference guide.)

Every

event handler function receives an argument event

holding an

Event object

with information

about the event, such as the x/y coordinates of the position where

the user clicked the mouse. In our event handler, we first generate a

random color and encode its red/green/blue components as 2-digit hex

numbers in a color string. We then create a circle with radius 50,

centered at the position where the user clicked. Here's an image of

the running program after I've clicked to create a few circles:

In many programs it's helpful to separate the code

into a model and a view. The model is a class (or set

of classes) that represent the state of the world and the rules for

updating state. For example, if we are writing a chess game, there

could be a model class Game that

represents the game in

progress. It might have a constructor Game()

that constructs a new game. It could also have methods such as

player() -

return the number (1 or 2) of the player whose turn it is to move

at(pos)

– return the piece that is currently at position pos

move(from,

to)

– make a move from square from

to square to

In a strict model-view architecture, model classes know nothing about the user interface. If we want to write several different user interfaces, we should be able to reuse the same model class(es) for each of them.

The view is a class (or set of classes) that is responsible for rendering the model, i.e. drawing the state of the world. Typically the view holds a pointer to the model.

In this form of architecture, there is sometimes an additional component called a controller that is responsible for processing input. When input arrives, the controller receives it and calls model methods to update the state of the world. Then someone (either the controller or the model, depending on the program) notifies the view that the state has changed and it's time to redraw it.

In my experience, a model-view architecture often leads to cleaner code than in programs where the model and view code are tangled together. I'd encourage you to use it when writing many graphical programs (or even when writing some programs with a textual user interface).

As an example of model-view architecture, let's write a program that lets two players play Tic-Tac-Toe. Our view will use a Tkinter canvas widget.

First let's consider the model. We will have a

single model class Game that represents

a game in progress. In our program we will have only a single

instance of Game. (If we wrote an AI

player for the game, it might create additional Game

objects representing hypothetical game states that it explores. We

will see how to do this in Programming 2 next semester.)

What methods should our Game

class have? We need an initializer to create a new Game.

We should also have a method move(x, y)

that makes a new move at a given position.

We will also need to have methods or attributes

that the view can use to learn about the current game state. We can

have a two-dimensional array at that

holds the contents of the board. Each element at[x][y]

will be an integer: 0 means the square is empty, or a 1 or 2 mean

that player 1 or 2 has moved there. (In theory we could instead use

strings such as ' ', 'X' and 'O'. However, strictly speaking even

that would be putting some knowledge of the view into the model. The

model is not supposed to know how the marks on the board will

appear.)

Additionally, let's have a boolean attribute

game_over that becomes true when the

game is done, and an integer attribute winner

that holds the player number who won, or 0 if the game was a draw.

Finally, since the view will need to display the winning squares,

let's have an attribute winning_squares

that holds a list of their coordinates.

Here is an implementation of the model:

class Game:

def __init__(self):

self.reset()

def reset(self):

self.at = [3 * [0] for _ in range(3)] # 3 x 3 array: 0 = empty, 1 = X, 2 = O

self.turn = 1 # whose turn it is to play

self.moves = 0 # number of moves so far

self.winner = -1 # player who won, or 0 = draw

self.winning_squares = []

def check(self, x, y, dx, dy):

at = self.at

if at[x][y] > 0 and at[x][y] == at[x + dx][y + dy] == at[x + 2 * dx][y + 2 * dy]:

self.winner = at[x][y]

self.winning_squares = [(x + i * dx, y + i * dy) for i in range(3)]

def check_win(self):

for i in range(3):

self.check(0, i, 1, 0) # check row

self.check(i, 0, 0, 1) # check column

self.check(0, 0, 1, 1) # check diagonal \

self.check(2, 0, -1, 1) # check diagonal /

def move(self, x, y):

if 0 <= x < 3 and 0 <= y < 3 and self.at[x][y] == 0: # valid move

self.moves += 1

self.at[x][y] = self.turn # place an X or O

self.turn = 3 - self.turn # switch players

self.check_win()

if self.moves == 9:

self.winner = 0 # draw

return True

else:

return FalseNow let's design the view. The board consists of a 3 x 3 grid of squares. Let's make the squares 100 pixels wide and tall. Additionally, let's plan to have a 50-pixel margin around the board. We could embed the constants 100 and 50 in various places throughout our code, but it's better to give names to them:

MARGIN = 50 # margin size in pixels SQUARE = 100 # square size in pixels

Our view class will have an attribute pointing to a Tkinter canvas.

(Alternatively, we could use inheritance rather than containment;

then our view class would be a subclass of the Tkinter Canvas

class. In this program I think either approach could be reasonable.)

In this and many other graphical programs, it is convenient to invent a custom coordinate system for our drawing. Let's use a coordinate system in which the square are only 1 unit high and 1 unit wide, and there is no margin. In this coordinate system the upper-left corner of the board will be at position (0, 0), and the lower-right will be at (3,0). Then, for example, the two vertical lines that form part of the board will extend from (1, 0) to (1, 3) and from (2, 0) to (2, 3).

In some graphics toolkits you can specify a custom coordinate system such as this one, and then all drawing commands will automatically work with those coordinates. Tkinter does not have this feature (and neither does Pygame), however we can simulate it easily. Let's write a function that maps an x- or y-coordinate in our coordinate system (which we will call user coordinates) into canvas coordinates:

def coord(x): # map user coordinates to canvas coordinates

return MARGIN + SQUARE * x

And now to draw at (x, y) in user coordinates, we need only draw at

(coord(x), coord(y)) in pixel

coordinates.

The built-in canvas methods that create lines, rectangles and ovals work in pixel coordinates. Let's make convenience methods that will do the same in user coordinates:

class View:

...

def line(self, x1, y1, x2, y2, **args):

self.canvas.create_line(coord(x1), coord(y1), coord(x2), coord(y2), **args)

def rectangle(self, x1, y1, x2, y2, **args):

self.canvas.create_rectangle(coord(x1), coord(y1), coord(x2), coord(y2), **args)

def oval(self, x1, y1, x2, y2, **args):

self.canvas.create_oval(coord(x1), coord(y1), coord(x2), coord(y2), **args)

In these methods, the notation **args in

each argument list causes Python to gather all keyword arguments

(such as width = 3, color = 'black')

into a dictionary. Then, in each method call the notation **args

causes Python to explode the args dictionary into separate

keyword arguments. And so the caller may pass any keyword arguments

they like to our helper methods, which will pass them on to the

underlying Tkinter Canvas methods.

When the user clicks we'll need convert the mouse position (in canvas coordinates) back to user coordinates, which will tell us which square was clicked. So let's add a helper function for converting in that direction:

def inv(x): # map canvas coordinates to user coordinates

return (x - MARGIN) / SQUARE

Our View class will have an attribute

game that points to the model. When the

user clicks the mouse, we'll call self.game.move()

to make a move. We will then want to update the view. As one

possibility, we could just draw what has changed, i.e. an X or an O

for the move that was just made. However, if the move won the game,

then we would also need to redraw all the winning squares to

highlight them in some way.

Instead, we will use a different approach: when

anything changes, we will redraw everything. I

recommend this approach in many graphical programs (especially those

with a model-view architecture). It will usually lead to the simplest

code. On a Tkinter canvas, we can call delete('all')

to delete all canvas items before redrawing.

Here is a complete implementation of the view:

import tkinter as tk

MARGIN = 50 # margin size in pixels

SQUARE = 100 # square size in pixels

BOARD_SIZE = 3 * SQUARE + 2 * MARGIN

def coord(x): # map user coordinates to canvas coordinates

return MARGIN + SQUARE * x

def inv(x): # map canvas coordinates to user coordinates

return (x - MARGIN) / SQUARE

class View:

def __init__(self, parent, game):

self.game = game

self.canvas = tk.Canvas(parent, width = BOARD_SIZE, height = BOARD_SIZE)

self.canvas.grid()

self.canvas.bind('<Button>', self.on_click)

self.draw()

def line(self, x1, y1, x2, y2, **args):

self.canvas.create_line(coord(x1), coord(y1), coord(x2), coord(y2), **args)

def rectangle(self, x1, y1, x2, y2, **args):

self.canvas.create_rectangle(coord(x1), coord(y1), coord(x2), coord(y2), **args)

def oval(self, x1, y1, x2, y2, **args):

self.canvas.create_oval(coord(x1), coord(y1), coord(x2), coord(y2), **args)

def draw(self):

self.canvas.delete('all')

for i in range(1, 3): # 1 .. 2

self.line(i, 0, i, 3) # vertical line

self.line(0, i, 3, i) # horizontal line

for x, y in self.game.winning_squares:

self.rectangle(x + 0.05, y + 0.05, x + 0.95, y + 0.95,

fill = 'green', width = 0)

for x in range(0, 3):

for y in range(0, 3):

if self.game.at[x][y] == 1: # draw an X

self.line(x + 0.1, y + 0.1, x + 0.9, y + 0.9, width = 3)

self.line(x + 0.9, y + 0.1, x + 0.1, y + 0.9, width = 3)

elif self.game.at[x][y] == 2: # draw an O

self.oval(x + 0.1, y + 0.1, x + 0.9, y + 0.9, width = 2)

def on_click(self, event):

if self.game.winner >= 0:

self.game.reset() # start a new game

else:

play_x, play_y = int(inv(event.x)), int(inv(event.y))

if 0 <= play_x < 3 and 0 <= play_y < 3: # valid square

self.game.move(play_x, play_y)

self.draw()

root = tk.Tk()

root.title('tic tac toe')

game = Game()

view = View(root, game)

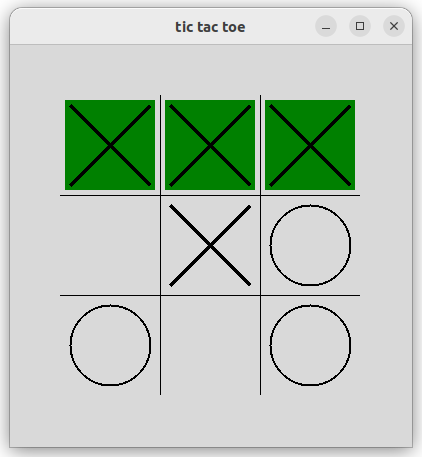

root.mainloop()The complete implementation (model plus view) is about 100 lines of Python code. Here is the program in action, where player X has just won the game:

Another popular graphics library is pygame. If you want to write a game or other program with real-time graphics, pygame may be a better choice than Tkinter.

For learning pygame I recommend two books by Al Sweigart:

You can read both of these books online for free. For that reason, I won't give a detailed Pygame introduction here. However, I have made a pygame quick reference page that lists many useful classes and methods. You may also wish to refer to the official Pygame web site and documentation, though it is not always so easy to find your way around it.

In the lecture we wrote a program that can display a bouncing ball using pygame. Here it is:

import pygame as pg

from pygame.math import Vector2

GROUND = 800

pg.init()

class Ball:

def __init__(self, pos, color, radius):

self.pos = Vector2(pos)

self.velocity = Vector2(0, 0)

self.color = color

self.radius = radius

def move(self):

self.velocity.y += 0.3 # apply acceleration

self.pos += self.velocity

limit = GROUND - self.radius

if self.pos.y > limit:

self.pos.y = limit - (self.pos.y - limit)

self.velocity = -0.7 * self.velocity

print(self.pos)

def draw(self, surface):

pg.draw.circle(surface, self.color, self.pos, self.radius)

surface = pg.display.set_mode((GROUND, GROUND))

ball = Ball( (400, 100), 'red', 50)

def draw():

surface.fill('lightskyblue')

ball.draw(surface)

pg.display.flip() # copy surface to actual window

clock = pg.time.Clock()

while True:

for event in pg.event.get(): #

if event.type == pg.QUIT:

exit()

ball.move()

draw()

clock.tick(30) # wait for next tick at 30 frames per second